Maclean’s Magazine:The Rise and Fall of a Chinese-Canadian Pop Star

Kris Wu, an ordinary kid from Vancouver, transformed into one of China’s biggest celebrities, with chart-topping albums, movie roles and lucrative brand partnerships. Then a series of social media accusations brought him down.

Yvonne Lau September 18, 2023

This article appears in print in the October 2023 issue of Maclean’s magazine.

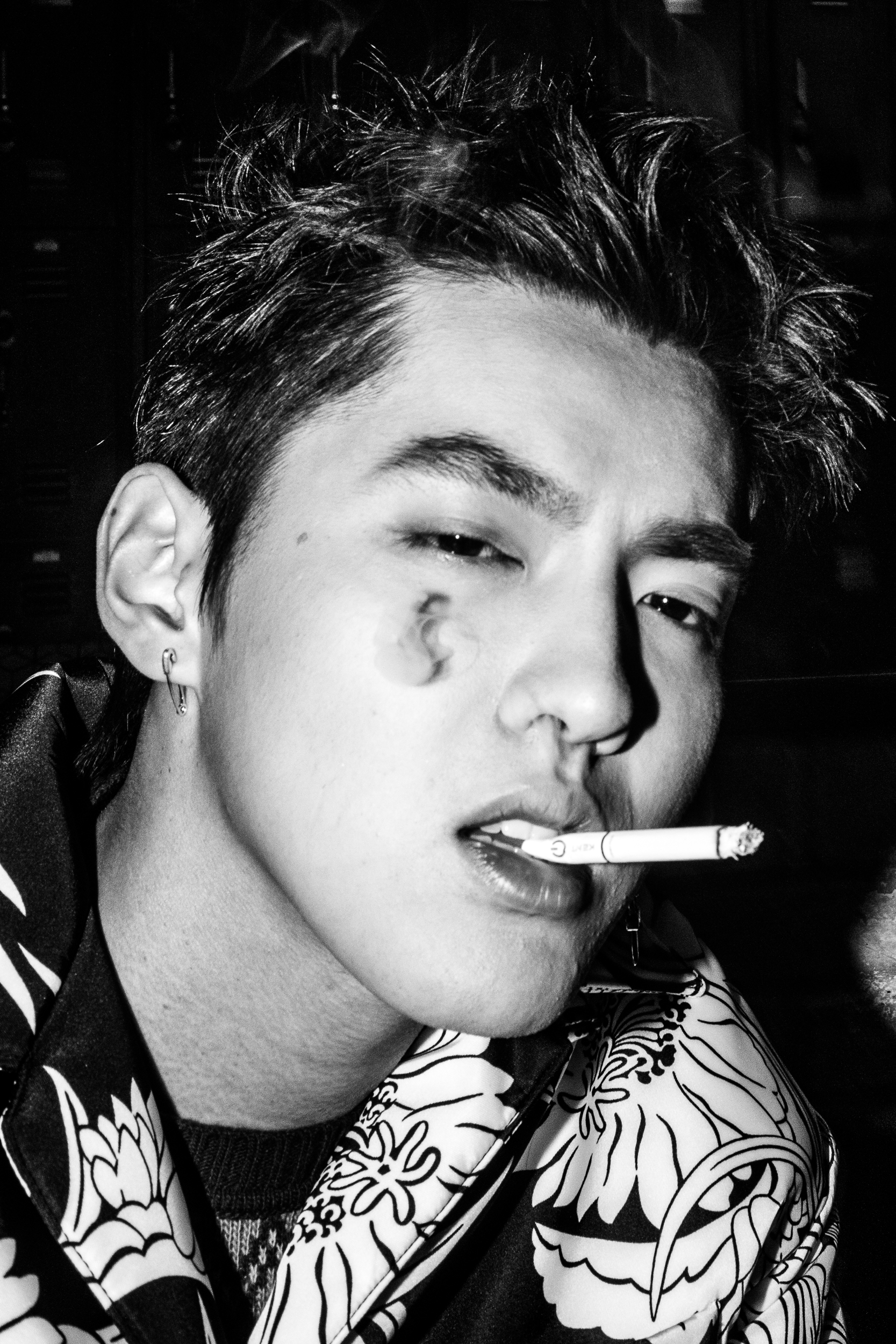

In November of 2018, the Chinese-Canadian pop star Kris Wu was at the peak of his fame: young, confident, unstoppable. That month, he released his album Antares, and the record was a phenomenon, with seven songs landing on the American iTunes top 10. Standing six-foot-one, with Cupid’s-bow lips and a V-shaped face, he was known as a Xiao Xian Rou, which in Mandarin Chinese means “little fresh meat,” a slang term describing the new generation of young male idols, revered for their delicate features and alabaster skin. And he was more than just a pop star: he landed film roles playing romantic heartthrobs and ancient action heroes, and he hosted and produced China’s first TV rap competition, The Rap of China, which drew 100 million viewers within a few hours of its debut and more than a billion by the sixth episode. At Madame Tussauds in Shanghai, a wax replica of Wu stood with figures of Vladimir Putin and Nicole Kidman. In the video for the song “November Rain,” Wu is decked out in a leather jacket and silver chains: “I’m a savage,” he sings in English. “I’m a good guy turned bad guy when I crossed the line.”

Wu’s bankability in China gave him a foot in the door to Hollywood. In 2017, he starred as Vin Diesel’s sidekick in a xXx movie and dropped a track with Pharrell Williams. He later collaborated with Travis Scott and Jhené Aiko and played NBA all-star celebrity games alongside Drake and Justin Bieber. He was unfathomably wealthy, with a collection of 21 exotic supercars and luxury homes in Vancouver, Los Angeles and Shanghai. But Wu was leading a secret double life, wielding his fame, looks and status to lure young women for sex. He seemed to get away with it for years—until a series of social media accusations brought him down for good.

In the mid-1990s, China loosened its emigration rules, allowing more people out of the country. At the same time, British Columbia’s government introduced policies to attract mainland Chinese immigrants. Between 1999 and 2009, Canada welcomed more than 30,000 new people from China per year, who comprised some 15 per cent of Canada’s total annual immigrants. Kris Wu was one of them. He was born Li Jiaheng in November of 1990, in the province of Guangzhou on China’s southern coast. His parents divorced when he was a toddler, and he subsequently had no contact with his father, nor did he ever mention his dad to his friends and classmates. In 2000, when he was 10, his mother, Stacey Wu Yu, moved them from Guangzhou to Vancouver. In Canada, Wu went by Kevin Li, using his father’s surname.

Wu landed in the city at a time when being Chinese was near-synonymous with wealth. Vancouver was a hub for China’s nouveau riche, people who had made their fortunes as the Chinese economy boomed and who longed for a more stable life and Western education for their children. But Wu and his mom weren’t rich, living in a small Vancouver apartment.

As the only child of a single mother, Wu grew up quickly. He saw himself as his mom’s protector. As soon as he turned 16, he got his licence to drive himself to school and back; he didn’t want his mom to have to take him. In high school, he held a job as a server at an Asian karaoke parlour, in part to relieve his mom’s financial pressure. “I didn’t want to always have to ask my mom for money, like when I wanted bubble tea,” he told a talk show host in 2016.

Stacey instilled traditional Chinese values in her son that sometimes chafed against his Western upbringing. She urged him to pursue practical fields, like medicine or law—but he wanted to be a basketball star. He spent his teenage years watching Allen Iverson on the court and downloading songs by Snoop Dogg, Jay-Z and Pharrell onto his MP3 player.

Midway through high school, Wu transferred to Point Grey Secondary School in Vancouver’s affluent Kerrisdale neighbourhood. The school is known for its famous alumni—both Seth Rogen and Nathan Fielder went there—and a student population that drove up to class in BMWs, Mercedes and Lexuses. At Point Grey, Wu befriended other Chinese-Canadian students and chatted with them in Mandarin. He wore his hair like his Chinese classmates, keeping his bangs long, covering one eye, and waxing his middle part high. “He looked and acted like a FOB, or fresh-off-the-boat, just like the rest of us,” says an ex-classmate of Wu’s, who had recently immigrated from Taiwan. (He and other former friends of Wu asked me not to name them to protect their privacy.)

But another side of Wu soon began to emerge. Sometimes he was a ride-or-die friend, while at other times he was vain and cocky, manipulating people for his own gain. A few months after his arrival, Wu began hanging out with guys in higher grades. He’d always viewed himself as more sophisticated than his peers, and these new social connections came at the expense of his old friends. “He looked down on us as if we weren’t cool enough for him,” a high school friend says. At one point, Wu befriended a group of Chinese students because he thought one of the girls had a crush on him. He borrowed notes and copied her homework. “If you were no longer useful, he would just ignore you like you were never there,” his ex-friend says.

What are the requirements for becoming a Canadian citizen? To become a Canadian citizen, you…

Writing a letter of invitation doesn’t mean you’re legally responsible for the visitor once they…

As of January 28, 2025, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) has updated the health…

The Super Visa is a multiple-entry temporary resident visa (TRV), issued with a validity of…

The Super Visa is a multiple-entry temporary resident visa (TRV), issued with a validity of…

If you applied for a new temporary resident visa, or a study or temporary work…